Download PDF Report: ACA Reinsurance Saves $ Billions

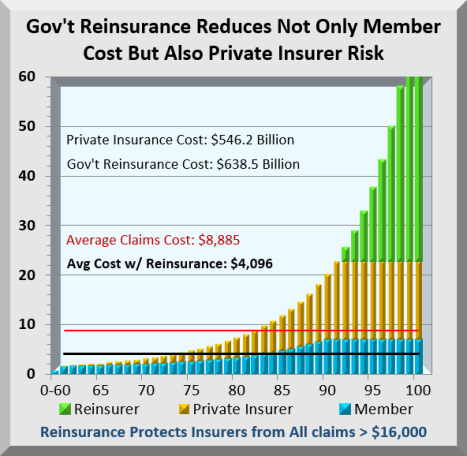

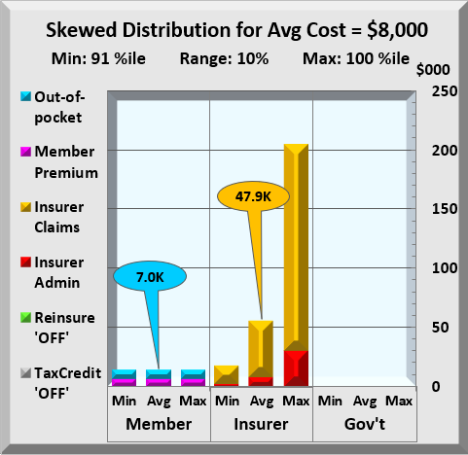

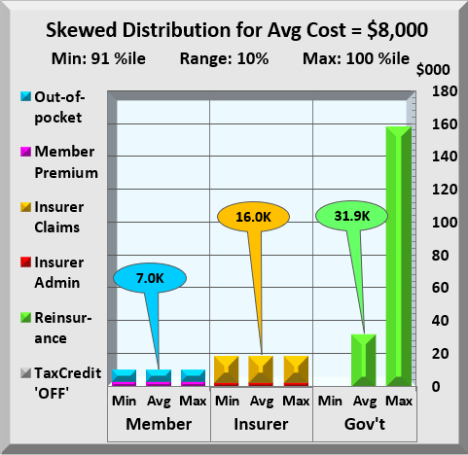

The chart below tracks ordered claims costs for 100 identically sized groups. About 60% of insured members never even reach their maximum deductible. On the other hand, costs at the highest end are off the chart. The gold bars in the chart are costs private insurers pay while the green bars are costs shifted from private insurers to Government. The blue bars are members’ Out-of-Pocket costs that reach the maximum allowed at about the 90% level.

Because of this skewing, Reinsurance costs more than private insurer costs at a $16,000 threshold, and will force premiums and costs down by over 50% for the entire industry.

Not only will this reduce health costs for millions, monthly savings continue. While initiated during the virus crisis, it is one Affordable Care Act amendment worth retaining.

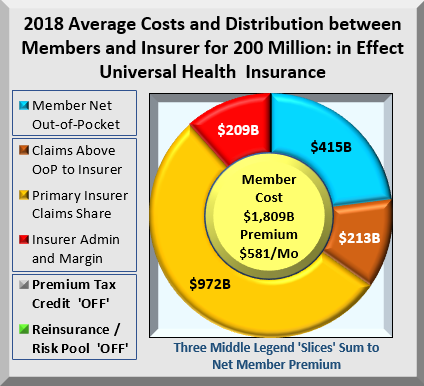

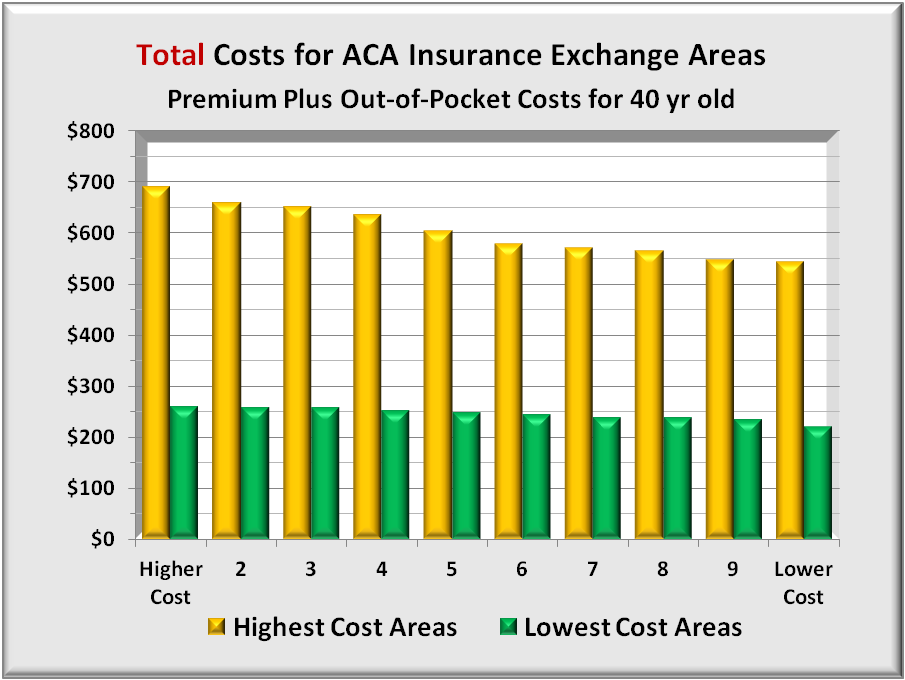

Base Case: This analysis uses a comprehensive Simulator to accurately track Affordable Care Act (ACA) Exchange processes and costs. A recent upgrade enables the Simulator to track costs for the whole country as Universal Health Insurance. Assumptions here apply to 156 million currently insured via work, plus 14 million Exchange insured, plus 28 million uninsured added for a total of about 200 million.

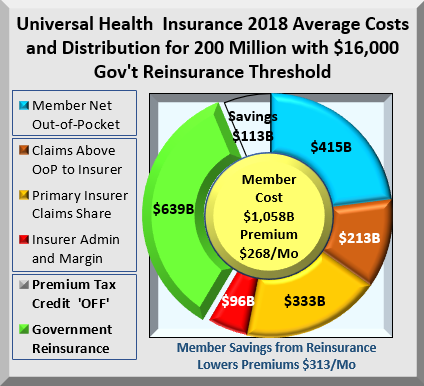

In the first chart below are cost distributions for 200 million insured where average healthcare cost is $8,000, deductible max is $1,650, and Out-of-Pocket max is $7,000. The Blue slice is Out-of-Pocket costs for member deductibles and copay. Copper is member copay for costs that exceed maximum Out-of-Pocket and shift back to insurers. Gold is insurer formula copay. Red is the mark up insurers apply to both Copper and Gold claims that they paid.

What many don’t realize is that ALL these insurers’ costs get transferred back onto members as premiums. Members pay for the entire chart, in this case, $1.8 Trillion. Not included in the base case are Premium Tax Credits. The legends above left describe the cost components for 200 million enrollees. The middle button shows average monthly premium of $581. But the real issue is shown below.

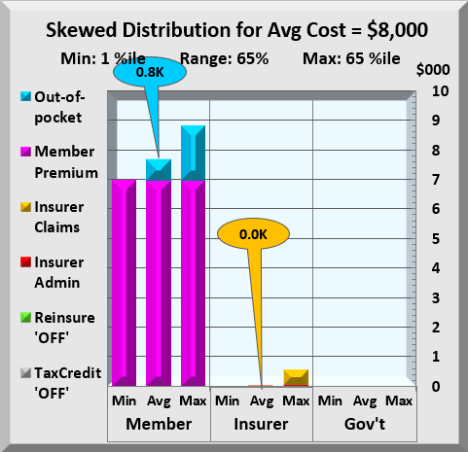

The chart above shows health costs from 1% to 65% split between member, insurer and Government. Average costs for insurers are almost zero, while members’ $800 of Out-of-Pocket costs are completely overwhelmed by premium. To have maximum effect of lowering members’ health costs, the focus should be on reducing premium costs. Government reinsurance does exactly that. It lowers total health costs a bit, but its real impact is to shift costs from member to Government.

Reinsurance Case: Reinsurance is not a new concept. The Out-of-Pocket max is a reinsurance threshold for individuals, above which all costs transfer to the insurer. Government Reinsurance is identical except it applies for insurers. Further, ACA included a temporary reinsurance program.

Prior to ACA, 35 states offered high-risk pools for those with pre-existing conditions. Their segregation of 2%-3% high cost individuals has two issues. They protect insurers from known costs but offer no protection from those who may incur high costs or already have unknown high costs. Also, separate risk pools often utilize different providers.

Simulator tests show that an $18,000 reinsurance threshold has similar financial effects as a 3% high-risk pool. However, since all members remain in the main pool, only the insurer, not the employer nor anyone else knows. It maintains complete HIPAA privacy on medical records and other health information. It also requires few administrative changes to implement reinsurance.

A $16,000 threshold rather than $18,000 drives premiums down by more than half. The chart below shows the impact of shifting all claims costs above it to Government. All dollar figures are per year. Monthly reinsurance costs are $53 Billion and monthly member savings are $76 Billion.

Reinsurance shifts $639 Billion while reducing health costs by $113 Billion. Where did the $113 Billion savings come from? ACA includes a minimum Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) that requires insurers to spend a minimum % of every premium dollar on claims. If claims decline, so must margins, which limits insurer profits. Having lower claims cost, insurers must also reduce their administration and margin amounts. The combination cuts member premiums by $313 to $268 per month, or over 50%. Of course, there is a cost to Government for covering excess costs.

Why are even shifted costs important? Because premiums consume a far greater percent of income from members with lower incomes. Health insurance is priced completely independent of income. For wealthy, health premiums are pocket change. Cutting premiums in half has a major effect on disposable income for lower income members.

Further, reinsurance doesn’t reduce any insurers’ costs until they reach the highest costs members as highlighted in the two charts below, both showing the costs of the top 10%. The callouts are the color-coded average cost for that range.

No Reinsurance Above / With Reinsurance Below

The upper chart tracks costs with no reinsurance. The lower chart has reinsurance employed. Without reinsurance, insurers claim costs jump to an average $47,900 compared to almost nothing for the lowest 65%. In the lower chart, with reinsurance, insurer costs dropped to an average $16,000 while Government shifted an average cost of $31,900 from insurer to itself. The chart below looks at the entire range.

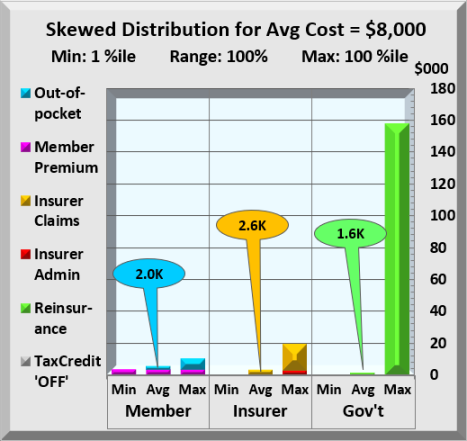

This chart is like the prior except that all members costs are included. Member Out-of-Pocket average $2,000 with premiums adding $3,200 to that cost. Insurers spend an average of $2,600, just $600 more than members pay. Clearly, Government reinsurance has a major impact first on insurers costs, which extend to members in the form of lower premiums. With economics favoring the great middle class, how would this be implemented?

Duration: The duration of the COVID-19 crisis has not been determined nor may it be soon settled. However, one can assume that other agencies will continue in crisis mode until some future date Government agrees upon. It is recommended that all or most of these provisions continue beyond the end of the crisis period.

Implementation: First, it extends the already existing Affordable Care Act (ACA) with its rules and infrastructure. In hindsight, several conditions were changed through the years that added complexity. Below are some conditions.

MLR – Medical Loss Ratio: MLR in its simplest form is a formula where claims are greater than or equal to 85% of premium. Through the years, both “claims” and “premiums” have had many fine “additions”. Going forward with this program, the original definition of claims and premiums will be used. Each is defined as follows:

Claims are defined as the accrued amount insurers record during the period. Excluded are any adjustments for IBNR (incurred but not reported) claims, nor any other adjustments other than material accrual errors.

Premiums are defined as income accruals insurers record during the period. Again, except for material accrual errors, all other adjustments are excluded from the premium definition. While some insurers will gain, the amounts are trivial compared to the complexity introduced with tracking and auditing all these other factors. Further, this returns to the original wording and intent of the ACA.

MLR is defined as a minimum of 85% of premiums. This will be uniform across the industry. The great majority of claims are already processed at 85% and any increased cost should be modest and at insurer’s expense during the crisis.

Premium Reductions: Insurers have 60(?) days to amend their claims processes to include Government reimbursements. During this crisis period, there will be 100% payments by Government for claims above threshold. Current period costs will be from January 1, 2020. Only after the crisis has ended may a small insurer copay be charged in lieu of reinsurance premiums. Insurers are also required to reduce premiums at least 50% for 2020 2nd half levels.

Employer Pass-Through: Most employers with health plans contribute variable portions of premium with employees paying the balance. Employers will be required to pass through their current contribution and adjust employee payroll withholding so the combined contribution equals the new insurer premium. Pass-throughs on policies that meet ACA coverage requirements will be listed as a separate income category on their W-2. Congress may choose to treat health premiums as an adjustment to gross income. This would save taxpayers from being taxed on this “income”. Employers already enjoy full premium deductions on their income. Why not employee, especially if it reduces AGI?

Administration: Primary insurers would remain responsible for vetting all claims. Government would enter Account Services Only (ASO) contracts with insurers for the administration of reinsurance. These entities would handle all the claims transferred from primary insurers. Government responsibility is for reimbursements to insurers.

Summary: The steps outlined here take full advantage of existing insurance infrastructure. It favors no income level, but reduces an extremely regressive premium payment system in effect today. It also significantly streamlines current processes that will reduce insurers’ costs. Further, it is not just a one-time payment but an ongoing savings, leaving more money for people to spend on necessities.

APPENDIX

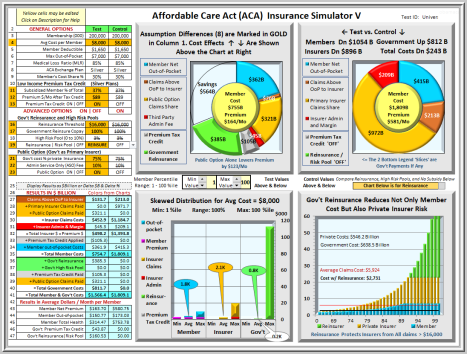

Below is a screen shot of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Insurance Simulator V. It shows savings and cost distributions for 200 million members with options configured for Universal Health Insurance including Premium Tax Credits. The General Options, Advanced Options, and Results tables are at left. The two charts are Test case and Control case. Both are the set to the size of the larger chart with savings shown as an “empty”. The bottom right bar chart uses Control values and can toggle between Reinsurance and High-Risk Pools. Extreme skewing is apparent with costs below 60% too small and the highest too big to chart.

The lower left chart separates lowest, average, and highest costs each for member, insurer, and Government. Their bar colors match the chart legend and results table colors. Just above the chart is a user configurable range of values to use in the bar chart. With extreme skewing of health costs, members bear the brunt of costs as premium while insurers and Government incur costs only at very high levels.

Titles and subtitles for tables and charts are dynamic and change to reflect the effects of option values. To help understand option descriptions and values click on any table description jumps to a Glossary tab with a full explanation of that item. A “Return” click brings you directly back.

The “Test” shown below is set for 200 million people, enough to insure everyone excluding Medicare and Medicaid. It includes Premium Tax Credits available to lower income members. It also includes Government reinsurance and a Public Option. These two options alone can drive down member premiums to $164 per month from $581 per month while lowering member costs by over $1 Trillion.

This Simulator is a Microsoft Excel program developed over multiple years and several thousand hours. It sorts health claims into 100 evenly sized groups. Their costs are run through a standard claims process that all insurers use. The claims process distributes those costs, Test and Control, between member, insurer, and Government. The Simulator incorporates over 5,000 formulas and adds six tabs of reference data.

For more information on the actual Excel program, email request to: KurzACA@gmail.com

This Excel program (1.5MB) contains no Visual Basic code or macros in which trojans, virus or other malware can be hidden.

With its thousands of computations, Simulator use on higher powered PC’s or laptops is recommended.

Download PDF Report: ACA Reinsurance Saves $ Billions

Filed under: ACA, Affordable Care Act, Analyses, Coronavirus, Covid-19, Crises, Health Insurers, Healthcare Reform, ObamaCare, Pandemic, Reinsurance | Tagged: ACA, Coronavirus, Covid-19, high-risk Pools, ObamaCare, Reinsurance | Leave a comment »

About healthreformtrends.com

Health Reform Trends, Research and Analysis Website

The analyses on this site rely primarily on data provided by non-partisan government agencies, long-established research institutions, and enterprises whose business is to analyze aspects of health care, be it health insurance or hospitals or health care providers. The following two paragraphs date back a number of years but are still valid.

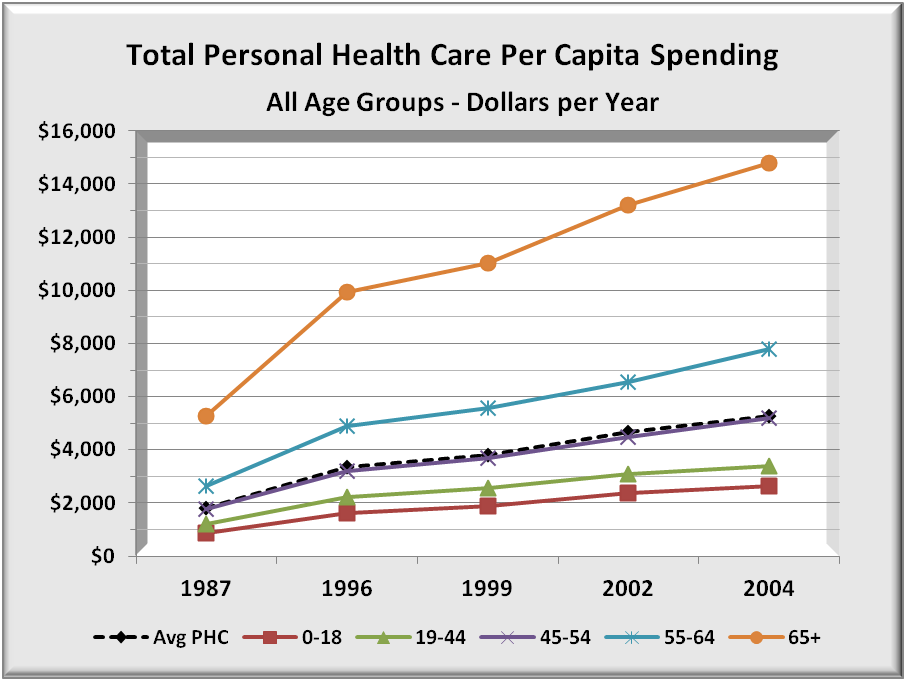

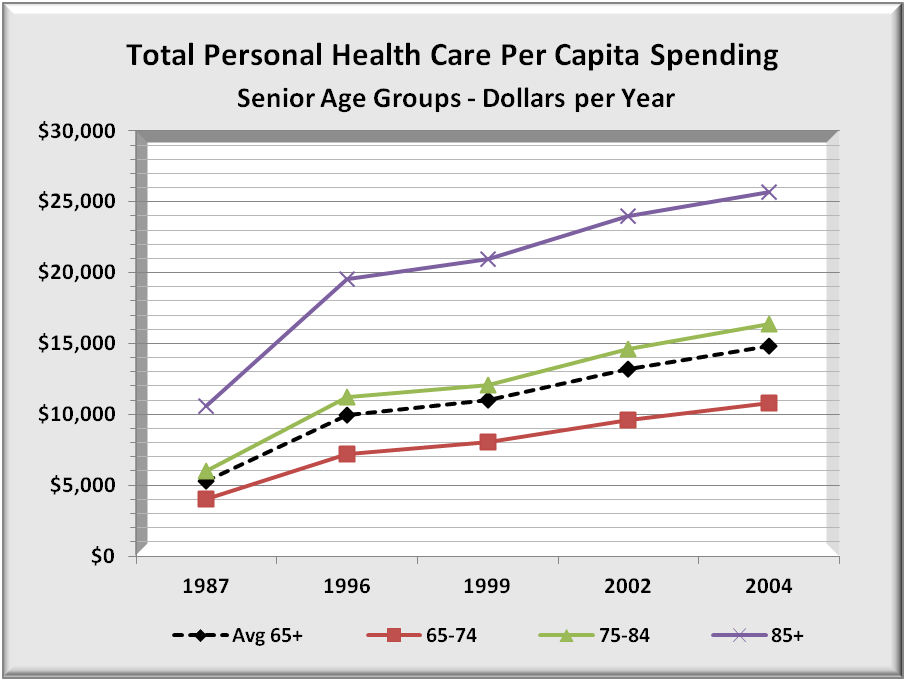

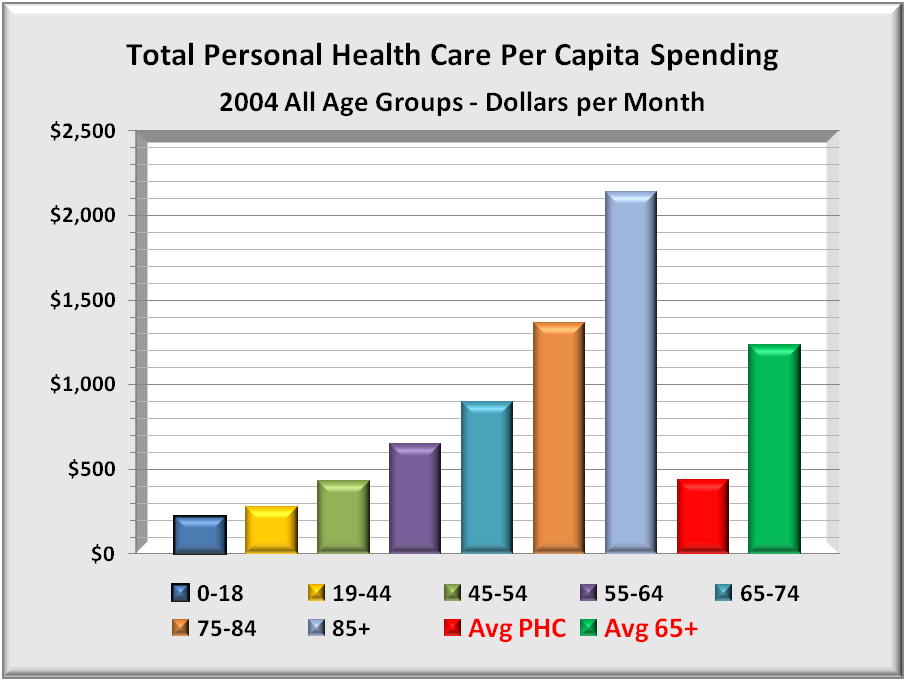

With the aging U.S. population, there will be a significant increase in demand for health care services. Under the status quo, these demands will place an extremely heavy burden not only on Federal and state governments but on citizens as health care costs continue to rise faster than inflation, wages, salaries, and benefits.

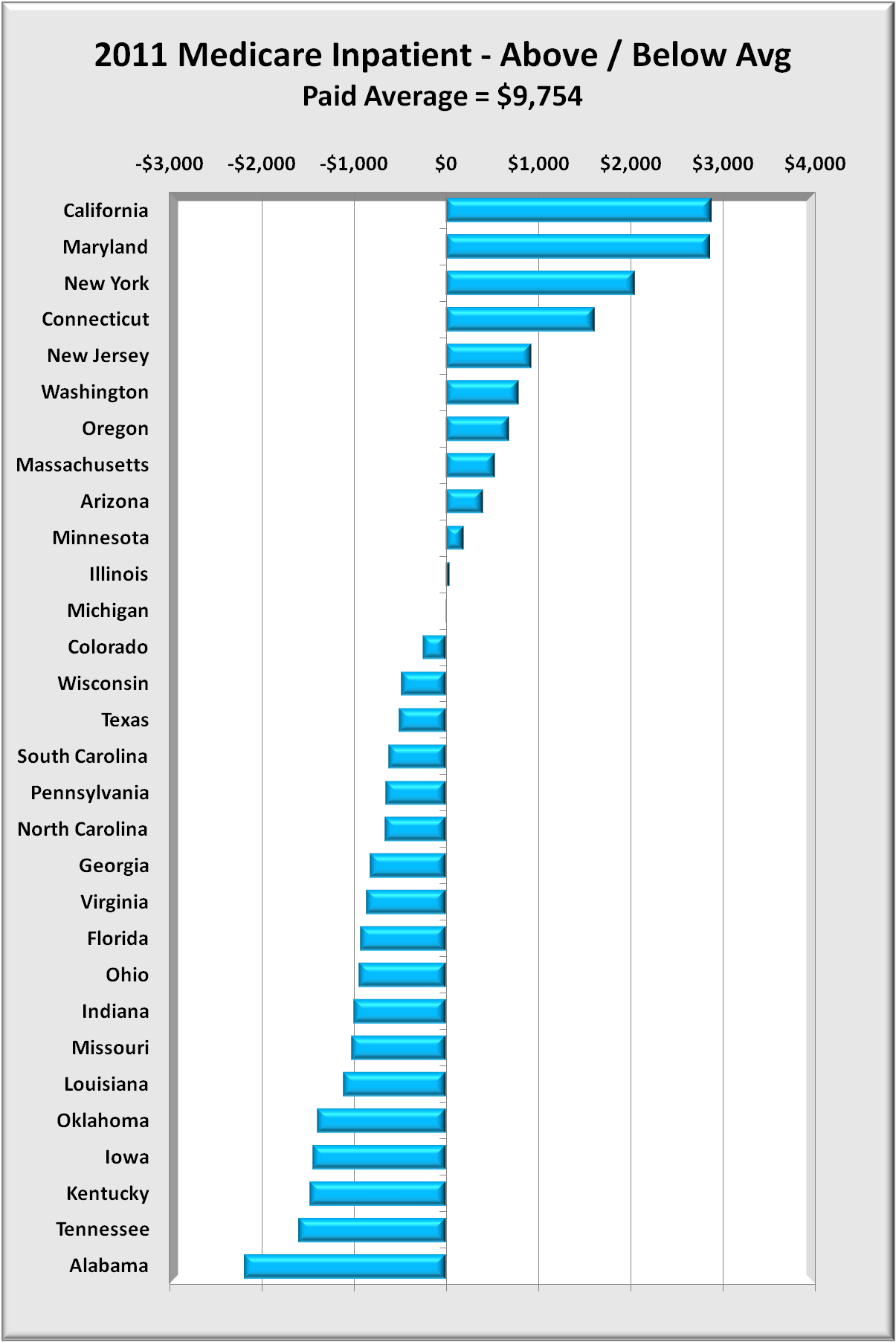

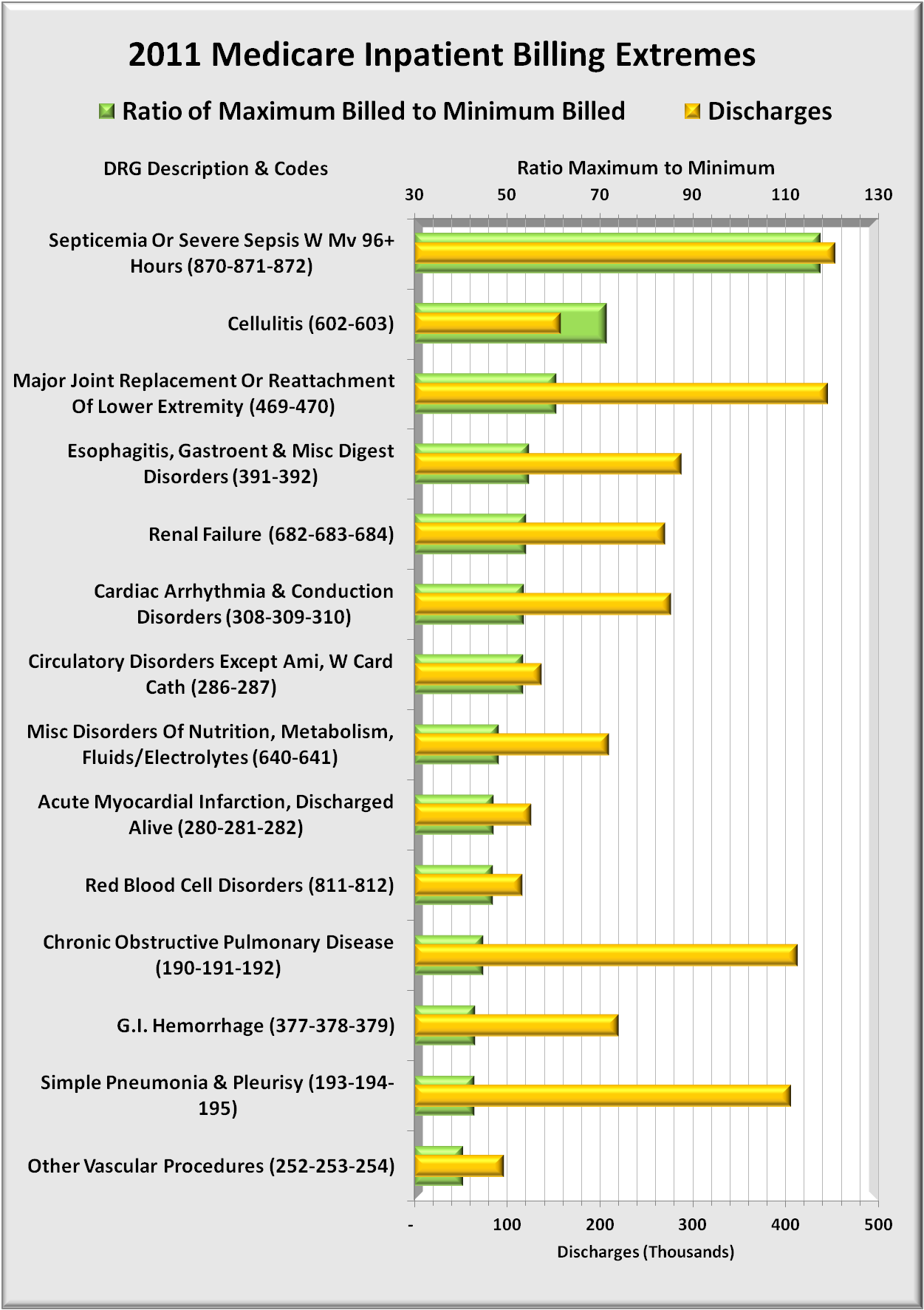

In 2011 there was an increased interest in 2011 on funding issues. In response, the site adds analyses dealing with wealth and income that may provide potential funding sources, not just for health care but to reduce deficits that have grown sharply during the “great” recession. Analyses focusing on income and wealth issues are now noted separately on the “Research-Analysis” tab on this website.

For more information about this site click on “About” tab.

For information about 8 ways to navigate to articles on this site click on the “Help” tab.

To read the full text of any article, CLICK ON THE TITLE.

Filed under: Analyses, Commentary, Congress, Government Health, Health Costs, Health Insurers, Health Quality, Healthcare Reform, Wealth and Income | Comments Off on About healthreformtrends.com