Download PDF Report >>> ACA Exchange Premium Extremes

SUMMARY

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created state run Insurance Exchanges to stimulate competition among health insurers. Some believe that private insurers are better suited to manage the complex health insurance market. But are they?

Kaiser Health News (KHN) recently published premiums that private insurers charge on ACA Exchanges. KHN identified 10 ACA Exchanges with the highest premiums, and 10 with the lowest. They found extreme differences and attributed them to competition or lack thereof. This analysis confirms those conclusions by comparing actual Medicare costs for those same areas.

Detailed cost data published by Medicare show that medical costs for seniors are fairly consistent across these 20 ACA Exchanges. Though costs for seniors are much higher than for those under 65, they provide a valid proxy for all medical costs when comparing one market area with another.

Medicare payments are based on service costs with pricing input from the American Medical Association. Medicare adjusts for regional differences so costs are consistent across the nation. Medicare essentially ignores hospital and doctor billing prices.

Private insurers, on the other hand, derive their costs more from provider billing prices which have been shown to be highly inconsistent. (http://insr.us/hospbill) Insurers do negotiate discounts from billing prices, but if the billing basis is inconsistent, it is harder to get a consistent result.

If there are few dominant providers, insurers have less leverage over discounts. If there are few dominant insurers, they are less inclined to aggressively set lower premiums.

Only one conclusion supports the enormous differences in premiums between the high and low cost ACA Exchanges. In areas where little competition exists, whether it be providers or insurers, private insurers are unable or unwilling to offer competitive pricing. The belief that private insurers are better suited to restrain market prices rings false in these instances.

METHODOLOGY

For years, health insurance markets have been divided into areas that coincide with county lines. The ACA insurance Exchanges continue to abide by these market boundaries.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) analyzed these “market areas” and found huge differences in ACA Exchange premiums. They identified 10 most expensive market areas and 10 least expensive areas (listed in Appendices 3 and 4).

ACA Exchanges insure people under 65, and premiums are derived from expected costs based on historical costs in the counties that make up each ACA Exchange.

Medicare publishes medical costs data down to the county level. Though Medicare costs apply primarily to seniors, one can map those costs to align with the 20 market areas. It does not matter that Medicare’s costs are much higher than for those under 65. The relative costs are what are important.

If two market areas have similar Medicare costs, it is fair to assume that medical costs for those not in Medicare will also be similar. Conversely, if Medicare costs are far different, one expects non Medicare costs will also be different.

Medicare data include all costs, while ACA Exchange data is only for premiums. Is this apples and oranges? Well no, because ACA requires insurers to offer plans identical in coverage and which differ only in cost sharing.

With identical coverage, the costs of each plan are identical. All that differs is the cost sharing. Plans called “Bronze” have premiums that cover 60% of expected costs, “Silver” which cover 70%, “Gold” – 80%, and “Platinum” – 90%.

Knowing this, one simply divides the premium by the percent coverage to derive total expected costs. If premiums for a silver plan are $280 per month, total expected costs would be $400 per month (280 / 70% = 400).

Since the KHN report applied to Silver plans for a 40 year old, premium costs were divided by 70% to get total expected costs. Direct cost comparisons can now be made between 40 year olds on ACA Exchanges and seniors on Medicare.

DISCUSSION

Kaiser Health News (KHN) recently published premiums that private insurers charge on ACA Exchanges. KHN identified 10 ACA Exchanges with the highest premiums, and 10 with the lowest. They found extreme differences but did not include an analysis of the causes.

The graph below shows monthly Silver Plan premiums for a 40 year old in the 10 LOWEST ACA Insurance Exchange Areas. As the labels at right show, those market areas occur over multiple geographic regions.

The green bar at bottom of the graph shows the average premium which is just over $170 per month.

Like the first graph, the graph below shows monthly Silver Plan premiums for a 40 year old in the 10 HIGHEST ACA Insurance Exchange Areas. Again the labels at right show those market areas occur over multiple geographic regions.

The green bar at bottom of the graph shows the average premium which is more than $400 per month.

Combing the highest and lowest, the graph below compares the monthly premiums, gold for the highest cost areas and green for the lowest. The differences in premiums are huge. The lowest ACA Exchange areas have average premiums less than half (about 40%) the premiums of the highest.

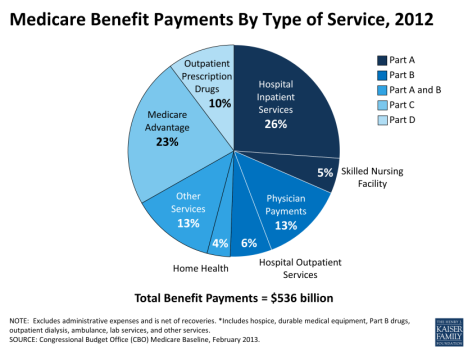

Having a direct comparison between high and low premiums, the next step is to compare all these 20 ACA premiums with another measurement common to all the same market areas. Medicare spending fits that bill, as it not only occurs in every area, it also comprises half of ALL medical spending in them.

This works only if Medicare costs are an appropriate proxy for ACA Exchange costs. To test, one needs comprehensive data on personal health care (PHC) spending by age group. Medicare provides that data which covers millions of people though only through 2004 as shown in the graph below.

The top line, seniors 65 and older, incurred a sharp increase in health care spending 1987 – 1996. Since 1996, cost increases have been proportional among all age groups. A closer look within Medicare age groups is done to assure Medicare is an acceptable proxy for all health care spending.

The following graph subdivides Medicare only costs into three age groups. The sharp rise in 1996 average cost was most affected by those 85 and older. Since 1996, all age group’s costs have risen proportionately. As cost trends for all age groups are similar since 1996, Medicare costs offer a good proxy for medical costs of other age groups as well.

The graph below combines the prior graphs of total Personal Health Care Spending per capita into seven age groups. The four left bars include all groups under 65 years old. The next three bars (aqua, gold and light blue) represent the three Medicare age groups. The last two bars on the right show national averages for all those under 65 (red) and all those 65 and older (green).

It is clear that health costs rise rapidly with age, accelerating more in senior years. The average costs for 40 year olds are included in the second (yellow) bar from the left which costs average less than $400 per month.

Averages for Medicare health costs, as shown in the far right green bar, are some three times greater than for 40 year olds. While this data is only through 2004, all medical costs have risen at about the same rate. One can expect Medicare costs today to still be about three times that of a 40 year old.

The above graph shows costs. To directly compare these total costs with ACA Exchange premiums, just covert premiums to total costs. As noted in the Methodology, divide premiums by 70% to get expected costs for each ACA Exchange.

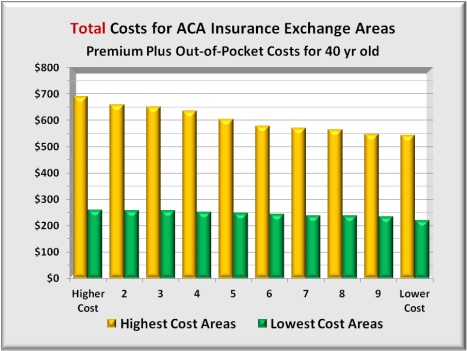

The next graph shows these total estimated costs for each of the 20 market areas. For the 10 most expensive areas, costs average about $600 per month. For the 10 least expensive areas, total average costs are about $245 per month, 40% of the high cost areas. The graph is the same as that for premiums above, but with 40+% higher monthly costs.

With total costs available for all, the graph below compares Medicare costs with costs of 40 year olds in each of the 10 lowest cost ACA Exchange areas. The low Medicare costs in the 4th series is Hawaii, which is the only outlier in this series.

In these competitive ACA Exchange areas, the average spread between Medicare and ACA is over four times. On a national average as shown above, the spread is around three times which shows competition really can reduce premiums.

Before comparing total Medicare costs with the highest cost ACA Exchange areas, it is helpful to know what Medicare costs are in the highest cost areas relative to lowest cost areas. The graph below shows Medicare costs in all 20 market areas. While there are variations in total Medicare costs between market areas, there are no trends that favor either high or low cost ACA Exchange areas.

The conclusion drawn from this graph is that high cost ACA Exchange areas have Medicare costs similar to low cost ACA Exchange costs. Nothing is inherently different for seniors.

The next graph compares total Medicare costs with total costs of 40 year olds in each of the 10 highest cost ACA Exchange areas. As expected, seniors’ Medicare costs are higher than are 40 year olds costs. However, with the national average spread around three times for this age group and Medicare, the difference here is one tenth of that, less than a 30%.

Since Medicare costs are not so different between high and low cost areas, the only conclusion is that ACA Exchange costs are too high. These high cost estimates have led to private insurer premiums far higher expected.

In conclusion, Medicare costs do not differ much between high and low cost ACA Exchange areas. By extension, health care costs for a 40 year old should not differ by much. Yet, the difference in premiums is huge.

If the insurer has near monopoly power, it has little reason to demand deep discounts. Insurers’ margins are constrained by ACA law to 20%. In short, 20% of a higher cost is more profitable than 20% of a lower cost. So why press harder for lower costs?

If the provider has near monopoly power, the insurer has little leverage since there are no competitive providers as an alternative. Either way, individuals in some ACA Exchanges are paying higher costs than expected.

Medicare doesn’t worry about either dominant insurers or dominant providers. It has a national payment scale, and with Medicare amounting to half a provider’s business, the providers are virtually forced to accept Medicare’s terms.

ONE SOLUTION IDEA

There is a solution that could remedy this situation. Amend the ACA with a proviso to apply only to any ACA Exchange market area in which the spread between insurers’ premiums and Medicare payments is greater than some threshold.

If the spread exceeds that maximum, ACA could create a public insurance option and where the public option requires providers to accept both Medicare and the option or neither. Public option premiums would key off Medicare payments plus an added profit margin to level the playing field with private insurers. This would force competition regardless of whether the insurer or the provider was dominant.

APPENDIX 1

One further check on Medicare as a proxy is a deeper dive into its major components to see if any are skewing total costs. The two graphs below highlight hospital admissions and emergency room visits per thousand beneficiaries in the 20 ACA Exchange areas. As expected, variations exist, but no consistent pattern appears between Medicare admissions between ACA Exchange areas.

There is one outlier and that is Medicare costs in the highest cost ACA Exchange area, a ski resort area. Here Medicare hospital and emergency room visits are markedly lower. It is likely that seniors living here may be more active in winter sports. This suggests they may be generally fit than the average senior, and thus incur fewer hospital and ER visits.

APPENDIX 2

Source for the 10 least expensive and 10 most expensive ACA Health Insurance Exchange areas were compiled by Kaiser Health News (KHN) from data developed by the Kaiser Family Foundation Program for the Study of Health Reform and Private Insurance, healthcare.gov, and ACA Exchanges. The costs analyzedwere for a 40 year old person.

KHN is a nonprofit news organization committed to in-depth coverage of health care policy and is an editorially-independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a non-profit private operating foundation, based in Menlo Park, Calif., dedicated to producing and communicating the best possible analysis and information on health issues.

APPENDIX 3: 10 Least Expensive Areas (Counties)

$154: Minneapolis-St. Paul. Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, Sherburne and Washington counties.

$164: Pittsburgh and Northwestern Pennsylvania. Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Crawford, Erie, Fayette, Greene, Indiana, Lawrence, McKean, Mercer, Warren, Washington and Westmoreland counties.

$166: Middle Minnesota. Benton, Stearns and Wright counties.

$167: Tucson, Ariz. Pima County.

$171: Northwestern Minnesota. Clearwater, Kittson, Mahnomen, Marshall, Norman, Pennington, Polk and Red Lake counties.

$173: Salt Lake City. Davis and Salt Lake counties.

$176: Hawaii. All counties.

$180: Knoxville, Tenn. Anderson, Blount, Campbell, Claiborne, Cocke, Grainger, Hamblen, Jefferson, Knox, Loudon, Monroe, Morgan, Roane, Scott, Sevier & Union counties.

$180: Western and North Central Minnesota. Aitkin, Becker, Beltrami, Big Stone, Cass, Chippewa, Clay, Crow Wing, Douglas, Grant, Hubbard, Isanti, Kanabec, Kandiyohi, Lac qui Parle, Lyon, McLeod, Meeker, Mille Lacs, Morrison, Otter Tail, Pine, Pope, Renville, Roseau, Sibley, Stevens, Swift, Todd, Traverse, Wadena Wilkin and Yellow Medicine counties.

$181: Chattanooga, Tenn. Bledsoe, Bradley, Franklin, Grundy, Hamilton, Marion, McMinn, Meigs, Polk, Rhea and Sequatchie counties.

APPENDIX 4: 10 Most Expensive Areas

$483: Colorado Mountain Resort Region. Eagle, Garfield and Pitkin counties, home of Aspen and Vail ski resorts. Summit County premiums are $462.

$461: Southwest Georgia. Baker, Calhoun, Clay, Crisp, Dougherty, Lee, Mitchell, Randolph, Schley, Sumter, Terrell and Worth counties.

$456: Rural Nevada Esmeralda, Eureka, Humboldt, Lander, Lincoln, Elko, Mineral, Pershing, White Pine and Churchill counties.

$445: Far western Wisconsin. Pierce, Polk and St. Croix counties. (across the border from St. Paul, Minn.)

$423: Southern Georgia. A swath of counties adjacent to the even more expensive region. Ben Hill, Berrien, Brooks, Clinch, Colquitt, Cook, Decatur, Early, Echols, Grady, Irwin, Lanier, Lowndes, Miller, Seminole, Thomas, Tift and Turner counties.

$405: Most of Wyoming. All counties except Natrona and Laramie.

$399: Southeast Mississippi. George, Harrison, Jackson & Stone counties. In Hancock County, the lowest price plan is $447.

$395: Vermont.* (Unlike other states, Vermont does not let insurers charge more to older people and less to younger ones. Its ranking therefore will differ depending on the ages of the consumers)

$383: Connecticut. Fairfield County. (The southwestern-most county, which includes many affluent commuter towns for New York City.)

$381: Alaska. All counties.

APPENDIX 5: Source-healthcare spending by age group:

APPENDIX 6: Source-Medicare Costs and Utilization by geographic area:

Table_State County_All_December 2013.zip from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

APPENDIX 7: Some Relevant Provisions of the Affordable Care Act.

It now appears that some market areas have less competition and the only way for an insurer to offer qualified plans is for ACA to ease a bit regarding condition (B) “ensuring sufficient choice of providers”.

Section 1311. AFFORDABLE CHOICES OF HEALTH BENEFIT PLANS (emphasis added)

1311(c) (1) Qualified Health Plans

(1) IN GENERAL.—The Secretary shall, by regulation, establish criteria for the certification of health plans as qualified health plans. Such criteria shall require that, to be certified, a plan shall, at a minimum—

(A) meet marketing requirements, and not employ marketing practices or benefit designs that have the effect of discouraging the enrollment in such plan by individuals with significant health needs;

(B) ensure a sufficient choice of providers (in a manner consistent with applicable network adequacy provisions under section 2702(c) of the Public Health Service Act), and provide information to enrollees and prospective enrollees on the availability of in-network and out-of-network providers;

(C) include within health insurance plan networks those essential community providers, where available, that serve predominately low-income, medically-underserved individuals individuals, such as health care providers defined in section 340B(a)(4) of the Public Health Service Act and providers described in section 1927(c)(1)(D)(i)(IV) of the Social Security Act as set forth by section 221 of Public Law 111–8, except that nothing in this subparagraph shall be construed to require any health plan to provide coverage for any specific medical procedure;

1311(c) (2) Rule of Construction

RULE OF CONSTRUCTION.—Nothing in paragraph (1)(C) shall be construed to require a qualified health plan to contract with a provider described in such paragraph if such provider refuses to accept the generally applicable payment rates of such plan.

.

Download PDF Report >>> ACA Exchange Premium Extremes

Filed under: Analyses, Health Costs, Health Insurers, Healthcare Reform, Kaiser Foundation, Medicare & Medicaid | Tagged: 40 year old, ACA, ACA Exchanges, Bronze, competition, cost sharing, Gold, Individual health Insurance, kaiser health, ObamaCare, Platinum, private insurers, Silver | Leave a comment »

MSNBC misses on Medicare reforms

Lawrence O’Donnell commented on Medicare reforms in Obama’s State of the Union speech. He seemed to imply that Obama was shifting from “fee for service”, the current model, to “capitation”, or HMO model. That is neither what Obama said nor implied.

What the Affordable Care Act (ACA) promotes is not the HMO or capitation model, but “payment for results”. This is something of a hybrid of “fee-for-service” and “capitation”. Fee-for-service IS unsustainable while a Medicare HMO would put the entire cost risk on the providers — both the risk [1] for the cost of each incident AND [2] for the frequency of incidents. That is too much risk for Providers. But there is a middle road.

“Payment for results” in the ACA “constrains” the cost for an incident but for NOT the frequency of incidents. So if twice as many seniors got the flu, providers would receive flu reimbursement for each senior treated. Just as occurs now, there is no added risk to providers if more people get sick or injured.

What changes is the reimbursement for an individual incident. “Payment for results” ends the one-for-one fee-for-service where hospitals and doctors are reimbursed a dollar for every eligible dollar billed.

However, Medicare’s “results” payments would apply only to combined groups of hospitals and doctors called “Accountable Care Organizations” (ACO). To encourage formation of ACO’s, ACA offers a carrot. If the ACO members working together can treat, for example, a flu incident for less, Medicare will first pay the ACO that lower cost but it will also share with the ACO the savings between billed cost and an imputed fee-for-service cost. Further, Medicare would make one combined payment to the ACO and not be involved in how the ACO divides that payment between hospitals and doctors.

Along with the carrot is a stick. If the ACO over-treated (higher cost) or mistreated that led to a relapse (poor result) and additional treatments, the ACO would not get reimbursed the full amount for these “extra” services. The ACO’s have a two-edged incentive to become more efficient.

With fee-for-service, efficient providers that bill less are paid less. Medicare keeps ALL the savings, so why should providers bust their butts to lower costs. Under ACA these ACO providers now get to share in the savings. This idea is not only good for providers and Medicare, but the entire health insurance industry. Providers are rapidly forming ACO’s across the country, not just for Medicare patients but for the entire population. Even some insurers are forming ACO’s, becoming both the insurer and provider.

For decades, hospitals or doctors have competed somewhat “softly” in that you never see price wars between providers. The business model of for-profit insurers closely mirrored the “cost-plus” model of some military contracts that led to $600 toilet seats. Insurers had limited incentive (or success) to put heavy pressure on providers. Instead, insurers spent more time cherry picking their membership to reduce claims instead of constraining provider costs.

Under ACA’s prohibition of excluding people with pre-existing conditions, insurers will no longer be able to cherry pick their membership. To compete, they will have to focus more attention on lowering provider costs. Hence, their incentive is also to promote ACO’s.

Finally, the ACA made payment for results a pilot program since this model is untested in the United States. Not being mandatory, the CBO has not factored in any savings arising from this program. The savings could be substantial and we have some evidence that savings will occur.

One analyses on this site, “Medicare – Fewer Benefits or Less Waste” compares Mayo Clinic’s all-in costs versus the highest cost 20% of hospitals. Mayo’s prices are higher than industry average, but their intensity was lower (fewer days, fewer treatments). If the 20% highest cost hospitals had costs comparable to Mayo’s, the savings could exceed $250 BIllion over 10 years. A significant savings indeed.

Filed under: Commentary, Health Costs, Health Insurers, Healthcare Reform, Medicare & Medicaid | Tagged: fee for service, MSNBC, payment for results, State of the Union | Leave a comment »