Download PDF Report >>> Medicare Waste

SUMMARY

If the highest cost 20% of hospitals were to cut in half the differences in price and utilization between them and the distinguished Mayo Foundation, and if all Medicare cost savings were proportional to Medicare cost savings of the last two years of life, annual savings could potentially reach $26 Billion. Over ten years and without cutting benefits, Medicare costs could be reduced by $260 Billion.

No one would complain about Mayo whose Medicare composite quality score ranks among the highest in the nation. Key to Mayo’s success has less to do with pricing than with utilization. Length of hospital stays and physician visits are significantly less than average, yet they handle some of the toughest cases in medical care. It is also noted that health care delivery in other countries is closer to the Mayo model than the more typical fee for service provider.

DISCUSSION

What senior would object to having medical coverage by the Mayo Clinic? The Mayo Foundation manages 20 hospitals in its network, and has a world-wide reputation as a very high quality institution handling the toughest cases. Less well-known, is that they provide this coverage at below average costs. For Medicare reimbursements within 2 years of death, Mayo costs average $28,000 per patient.

This sounds expensive, and it is. However, the national average to cover the last 2 years costs was just over $30,000. Multiply that by 930,000 average (2001-2005) annual Medicare deaths and Medicare costs for just this segment are about $28 Billion per year. This is some serious money. The first question is where is it going?

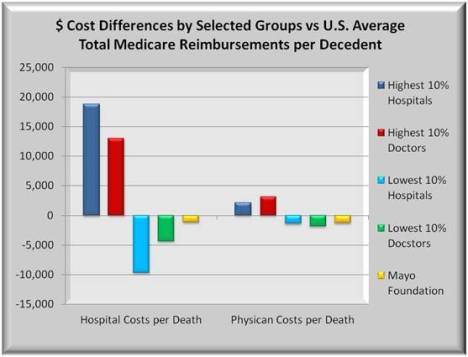

The following graph consists of two groups of bars. On the left are hospital cost differences from U.S. average for the highest and lowest 10% of hospitals, and the highest and lowest 10% of physicians. The 5th bar in each is Mayo. The bars at right are the same except they show physician cost differences from average.

The highest 10% of hospitals incur nearly $19,000 more hospital costs compared to the U.S. average while the lowest 10% of hospitals incur almost $9,000 less than the average, a high/low difference of $28,000. Physician cost differences are similar, but the magnitude in dollars is smaller.

Costs become even more serious when one considers quality scores. Hospitals whose costs are in the top 10% of all hospitals had lower average quality scores. Yet, their costs were more than $50,000 per patient. Similar results occur for hospitals sorted by Physician costs. In all cases, higher cost providers had lower average quality scores than lower cost providers. In short, more may not mean better as shown below

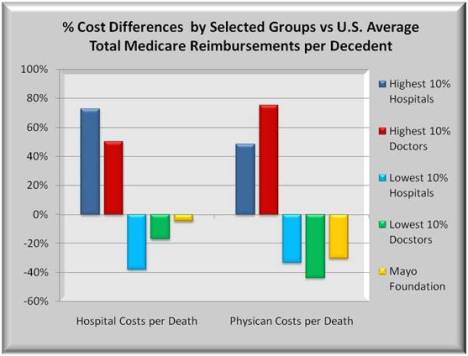

So how do providers like Mayo Foundation and other similar quality hospital and physician systems attain such high quality scores while holding the line on costs? It may help to first show these costs as percent differences between the highest and lowest cost providers. The graph below uses the same data from the 1st graph but presents cost differences as a percent.

Those hospitals and physicians whose costs are in the highest 10% are nearly 75% above average, while those with lowest costs are more than 30% below average. Mayo’s hospital costs are slightly below average but its physician costs are significantly lower.

Seniors are worried that proposed reforms and reductions in Medicare spending will reduce benefits. A greater worry should be why there are such large reimbursement disparities now between providers. Either some are being over-served or others are being under-served. Neither should be acceptable.

Medicare recipients might rightly ask, since all people pay into Medicare at about the same rate, why isn’t the payout more evenly distributed between high and low cost providers. The difference between the highest and lowest hospitals and physicians almost equals the average cost of $30,000 per patient. Despite the huge cost differences, the result is the same. The patient died.

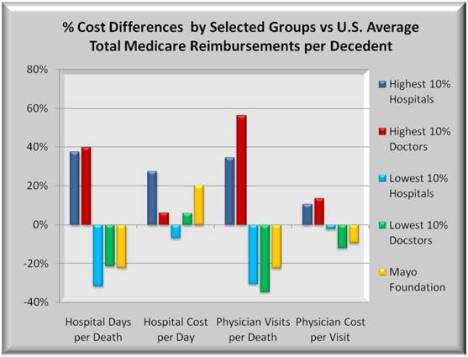

Just as showing percents is more meaningful than dollars, the above cost differences can be further broken down into two components. One component is price and the other is volume or utilization.

Remember when gas prices were over $4.00 per gallon? People cut back on driving so their gasoline consumption (volume) went down. Fewer miles driven helped people offset some of the high price per gallon. A similar outcome occurs in healthcare.

Hospital costs are affected by the cost per day (price) times how many days a patient stayed (volume or utilization). For physicians, the analogy is the cost per physician patient visit (price) times the number of visits by the physician (volume). Volume times price equals total cost, and “all in” costs equal total hospital costs plus total physician costs. The graph below shows the four components of price and volume.

Hospital Volume (utilization – length of stay)

The first group of bars shows differences in hospital days. Patient stays at the most expensive hospitals were nearly 40% more than average while those at the least expensive hospitals were some 20% less than average. From a utilization view, there is a significant difference in hospital (days) at higher cost hospitals. Higher cost hospitals tend to be larger, more complex and more intensive. Yet, Mayo hospital days are comparable to the lowest cost hospitals.

Hospital Price (average daily cost)

The second group of bars shows differences in Hospital cost per day, or pricing. Here both high cost hospitals and Mayo are more than 20% above average reflecting the sophisticated and expensive equipment and procedures performed. In hospitals where physician costs are high or low, hospital pricing tends closer to the national average. But Mayo more than not offsets their higher daily hospital costs with shorter length of stays. The higher cost hospitals compound higher prices with more lengthy stays for a total hospital cost 75% higher than average.

Physician Volume (visits) and Price (cost per visit)

The remaining two groups show differences for physician volume and price. Visits at high cost hospitals deviate even more from average than length of stays. Physician visits at low cost hospitals mirror shorter hospital stays. Physician costs per visit do not vary nearly as much as do hospital costs.

With regard to Mayo, utilization is also below average (fewer visits), but here physician pricing (cost per visit) is also below average. Combining fewer patient visits AND lower costs per visit, yields a cost difference 30% below average for Mayo.

Medicare Reductions Need not Lower Benefits

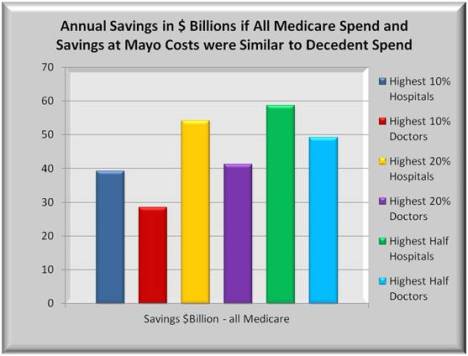

What conclusions to draw? Some legitimate cost differences should be expected. But data suggests that if the high cost hospitals changed some of the care delivery nearer to Mayo’s performance, significant savings could occur with NO loss in benefits. The graph below shows the potential savings if these higher cost hospitals had the same price and utilization structure as Mayo. If the cost structure of the top 50% of all hospitals were the same as Mayo, annual savings would be nearly $4 Billion.

But there is more. The savings described apply only to the Medicare costs associated with the last 2 years of patient life. Those costs were noted at some $28 Billion per year. However, Medicare annually reimbursed over $400 Billion in total. If total savings were comparable to the last two years of life costs, the savings could be 15 times larger than in the above graph.

The graph below shows a 15X multiplier effect with annual savings for 6 groups of hospitals: the highest 10%, 20% and 50% of hospitals filtered on total hospital costs. Plus a similar 10%, 20% and 50% of hospitals filtered on total physician costs. Significant in this graph is that the differences between the highest cost and the more average cost hospitals are fairly extreme. If one were to focus reform efforts on just these extremes, Billions could be saved.

The graph shows total theoretical savings. A more reasonable assumption would be to halve the theoretical savings. Thus, if the highest cost 20% of hospitals were to cut in half the differences in cost and utilization between them and the distinguished Mayo Foundation, and if all Medicare cost savings were proportional to Medicare cost savings of the last two years of life, then the annual savings could potentially reach $26 Billion. Over ten years and without cutting benefits, Medicare costs could be reduced by $260 Billion. Actually achieving this level of savings would be a challenge. But Billions of dollars in waste, fraud and abuse could be safely removed without affecting real benefits.

Why will those levels of savings not likely occur? It would require hospitals, physicians and insurers to change their “business model” to achieve significant savings and that is a very broad challenge. There needs to be a major shift from the “fee for service” model where every procedure, item and encounter are tracked and billed, to a more managed care model.

Insurers are familiar with managed care in the form of HMO policies. In HMO’s, the risk is on the insurer that premiums that are fixed per enrollee are sufficient to cover the health care costs of enrollees. Some insurers are also providers so they would carry the insurance risk as well as the provider risk.

For health care providers, the risk of managed care is similar. For any specific encounter, like an appendectomy, the provider is paid a fixed amount from the insurer, and the hospitals and physicians are responsible for dividing up the payment and are at risk to deliver quality patient care for that amount.

While much focus has been on insurance reform to make it available to more people, attention must also be paid to wringing waste and abuse out of the system. Some of the currently proposed Medicare reforms include pilot programs to gradually shift the heavily “fee for service” orientation towards manage care. In fact, of the 1,000 pages in House bill 3200, half are devoted to reducing waste in Medicare and Medicaid and pushing towards less skewed reimbursements than exists in the current environment.

Notes

Sources

Dartmouth 2005 Atlas of Health Care DAP_Hosp_HRR_ST_01_05.xls

Table 1. Hospital information (2001-05) – Number of deaths among chronically ill patients assigned to hospital

Table 2. Medicare spending per decedent by site of care during the last two years of life (deaths occurring 2001-05) (HOSPITAL)

Table 3. Medicare Part B spending by type of service (BETOS category) per decedent during the last two years of life (deaths occurring 2001-05) (PHYSICIAN)

Table 4. The Medical Care Cost Equation: Disaggregation of hospital (facility) reimbursements per decedent into contributions of volume (patient days per decedent) and price (average reimbursements per day in hospital) during the last two years of life (deaths occurring 2001-05)

Table 5. The Medical Care Cost Equation: Disaggregation of payments for physician visits per decedent into contributions of volume (physician visits per decedent) and price (average payments per physician visit) during the last two years of life (deaths occurring 2001-05)

Table 6. Resource inputs per 1,000 decedents during the last two years of life (deaths occurring 2001-05)

Table 8. CMS Hospital Compare technical process quality measures (all patients, 2005) (QUALITY COMPOSITE SCORE)

Centers for Disease Control: Table 128. Personal health care expenditures, by source of funds and type of expenditure: United States, selected years 1960-2006

Download PDF Report >>> Medicare Waste

Filed under: Analyses, Healthcare Reform, Medicare & Medicaid | Tagged: fewer benefits, length of stay, less waste, Mayo, mayo clinic, physician visits, utilization | 2 Comments »

Government Bureaucracy?

Download PDF Report >>> Government Bureaucracy

Some people say any Government health plan is a huge bureaucracy. Below are two application forms for personal health insurance. The first is representative of private insurers. The second is from the Government. Help me out here. Which one is the bureaucracy?

Private insurer Personal Health Insurance Application Form

8 pages of questions

Government Medicare Personal Health Insurance Application Form

8 questions

Download PDF Report >>> Government Bureaucracy

Filed under: Commentary, Health Insurers, Healthcare Reform, Medicare & Medicaid | Tagged: bureaucracy, government insurance, Private insurance | Leave a comment »